EARLY HISTORY

Stone Age (Neolithic) Celtic Barrows: Deadmen’s

Graves are three Celtic Barrows near Claxby St

Andrew which was/is in the parish of Well.

For more information click here

Spellow Hills, Ulceby

Cross

The badly damaged

long barrow of Spellow

Hills, or to give it its more evocative name, 'Hills of the Slain' stands at a height

of 90 metres above sea-level on the side of a south facing valley. It is said that

because of damage, possibly caused by people digging for treasure or the

collapse of an underlying wooden mortuary structure, that the 18th century

Lincolnshire antiquarian William Stukeley mistakenly thought the site to be a

line of round barrows which is understandable.

Bronze Age: There is a round Barrow at

Mill Hill in Caxby St Andrew too.

Roman Settlements: Well is very close

to a settlement to the west at Ucleby

Cross and Willoughby to the north east

(Roman name Verometum).

There is evidence of a pottery near Well

during the Roman occupation. To read

about this pottery click here.

According to The History of the County

of Lincoln, From the Earliest Period to

the Present Time by Thomas Adam

pub.1834

“Near this place in 1725 two urns

containing six hundred Roman coins

were found.” and “In the neighbourhood

are three celtic barrows contiguous to

each other.”

There is no indication of what happened

to the coins.

In Roman times the sea started around Burgh-le-Marsh (Skegness was under

the North Sea) and the route from Lincoln (a cross roads of the Fosse Way

and Ermine Street) to the coast was around a body of water between the

Wolds and Lincoln. Down through Ulceby Cross. With Global warming there

are predictions that the sea level will rise back to these levels. At the time the

Romans were in Britain it was very warm, rather like Italy now, grass grew all

year round so there was no need to grow crops to feed animals in the winter.

The weather becoming colder is thought to be one of the reasons the Romans

abandoned Britain, it was just not possible to grow enough food to feed a big

army.

There is a record of some Roman coins being found in Well.

Click here for the information

Invasions from Nordic areas brought new settlers and by 886 the Wolds had

become part of Danelaw.

Although we call them the ‘Dark Ages’ actually quite a lot was happening in the

centuries following the Romans departure. Life may have been harder but

people adjusted.

About 4 miles from Well near Scremby an Anglo Saxon cemetery containing

49 burials was found by a Metal Detectorist in 2017.

Click here to read about the discovery of the graves and their grave jewellery.

1066 Norman Conquest

The deserted medieval (Medieval - 1066 AD to 1539 AD) village of

Laysingthorpe (or Laisintorp), was probably in or near Scremby, and Roman

pottery was found there in 1958.

The Anglo-Saxons didn’t own land, ‘might was right’ then, but after 1066 the

Normans, in 1086, decided to record all the land and people in the county and

Well was one place worth recording. The land was split into 4 parts, Ailby,

Rigsby, Tothby and Well.

There is a natural spring at the western end of the upper lake which has never

been known to freeze, and which since the 18thC has fed the two lakes. The

medieval church and village were built on high ground to the north-west of the

spring directly across the upper lake from where the house now stands.

In the Middle Ages it was the seat of a powerful Norman family. The

Descendants of Ragemer le Welle, who held the manor in the Doomesday

Book, as a sub-vassal of Gilbert de Gaunt. John, Lord Welles, wa sent by

Richard 11 as Ambassador to Scotland in 1395. His son was a leader of the

abortive Lincolnshire Revolt in 1420 after which Well was confiscated, but

restored later. Joh,9th Baron and 1st Viscount Wells, made a brilliant royal

marriage which the second daughter of Edward 1V but had not heirs. Well

then passed in 1490 to Lord Willoughby de Resby. The 11th Lord Willoughby

was created Earl of Lindsey in 1626, a key figure in the Royalist side in the

Civil War and was forced to sell the estate in 1652 to it’s occupant - the

Parliamentarian Colour William Wolley. The Wolleys were allowed to keep

their land after the Restoration but in 1695 sold them to Anthony Welden, and

explorer-trader who had grown rich in the employment of the East India

Company and as the first president of Fort William (later Calcutta).

The Great Plague

Alford knew the ‘Black Death’ before London

From the Grimsby Telegraph Live

3/12/22

The Great Plague of London has

occupied English historians to such

a degree that similar events in other

parts of the country have almost

been forgotten.

A study of modern school books or a

visit to a public library could easily

give the impression that London was

the only place ever to have been

plague-stricken.

Unfortunately for our ancestors, this is not so. Before and after the London

plague of 1665, many Lincolnshire towns and villages were subject to the

Black Death.

At Thornton Curtis in 1593 there was a dramatic rise in the mortality rate.

Ninety funerals were recorded in only three months – a tremendous number

for the small population of that area.

Although the words “Incipit Pestis” were not written into any of the burial

records, there cam be little doubt that some form of plague was responsible for

many of the deaths.

In Great Coates in 1670 there were 25 burials – twice the annual average for

the parish at that time.

This was such an unusual occurrence that the Rector, Thomas Doughty, put a

memorandum in the parish register saying: “There was a great mortality this

year. Most of them that died were taken off in a very few days’ sickness.”

One place in the county that appears to suffered more than any other from the

pestilence is Alford.

Miles Cross Hill, looking towards Alford, pictured in 1966. When the plague

struck Alford this was the spot where money was left for food.

Miles Cross

Hill, looking

towards Alford,

pictured in

1966. When

the plague

struck Alford

this was the

spot where

money was left

for food.

Thirty-five years before the London epidemic, Alford was cut off from the rest

of the county by plague.

The first death to have “Incipit Pestis” recorded alongside it took place in July

1630.

After that date the Vicar of Alford, George Scortreth, conducted several

funerals each week; and dutifully entering the details in the register, he

perhaps never realised that he was writing a page of county history.

Bad news travels fast in any era, and the cry of “Plague” in the 17th century

was no exception.

Once it was known that there were

plague deaths in the town, the people

of the surrounding countryside looked

on Alford as a place to be avoided.

Right: With the 'Plague Stone' in the

garden of her Tothby Manor home is

Mrs Barbara Willoughby. In 1630 Alford

was isolated by the plague, and the

stone was where people from outside

sold goods to the townsfolk. The hollow

was filled with vinegar to purify their

money.

With the 'Plague Stone' in the garden of

her Tothby Manor home is Mrs Barbara

Willoughby. In 1630 Alford was isolated

by the plague, and the stone was

where people from outside sold goods

to the townsfolk. The hollow was filled

with vinegar to purify their money.

Anyone daring to leave the town would

have a poor sort of welcome from the

countryfolk.

Very soon after Alford was isolated, the shortage of food began to be a

problem. Although the people in the country districts had produce to sell, no

one would venture into the town.

Eventually, it appeared that starvation would be as much a cause of death as

the plague. a solution to the problem was found, however.

The people of Alford went out and placed money on a stone on Miles Cross

Hill, overlooking the town, then they retired while the country folk exchanged

food for the cash.

This method of supplying the town went on throughout the summer the plague

raged.

There were 22 deaths in July, 47 in August and 26 in September.

The worst day of all was August 20, when five people were interred at one

time.

Some families were almost wiped out by the disease. One man, Thomas

Brader, and five of his children all died within a fortnight.

In September, the Vicar had the sad task of adding the name of his daughter,

Rebecca, to the list of victims.

When at last winter came, the plague began to release its grip. As the

temperature dropped, so did the death rate.

Alford was free from the plague. And one of the more sombre pieces of the

Lincolnshire patchwork was complete.

Into Georgian Times

The turning point in the history of Well came about in 1720 when James

Bateman, second son of Sir James Bateman of Shobden Court, Herefordshire,

acquired the estate.

The circumstances are not clear but there was a close relationship between

the Bateman and Chaplin families. Sir Robert Chaplin, son of a Lord Mayor of

London and a director of the South Sea Company, had sold Shobden to his

fellow city merchant Sir James Bateman. Sir Robert Chaplin estates were

mostly in Lincolnshire. He was MP for Grimsby from 1712 to 1720 Sir Robert

was ruined by the South Sea Bubble in 1720 and it is possible that when the

youngest Jams Bateman married his only daughter Ann the following year, the

Well estate came as her dowry in lieu of ready cash. The old man was to live

at Well with his daughter and son-in-law for the last seven years of his life and

his hatchment dated 1827 still hangs in the Church.

James Bateman (the younger son) either purchased or inherited the estate

and house.

By all accounts James Bateman lost little time in rebuilding Well, but

unfortunately few papers from this period survive. In 1727 he was

exchanging pieces of land with the Massingberds (Gunby Hall/Bratoft Manor)

in order to made his estate more of a unit. In 1729 he purchased the manor of

Claxby from Lord James Cavendish.

It was probably around this time that moved Well village to the edge of the

park, dammed the stream to make two serpentine lakes and built the new

house on a rise between the two on the old manor.

The new house was certainly finished by 1744 when the new Church was built

(see the page about the church on this web site). In 1733 Ann died leaving

him with just a daughter and his building stopped at this point.

It has been suggested that the architect was Thomas Archer. Archer married a

Chaplin of Tathwell, Ann, Bateman’s first cousin. Others have suggested

Flitcroft, an architect who was amongst the same group of people involved

with the two families.

A crucial part of the landscape of Well is played by the Church. The old

church stood on the other wide of the upper late and was described ‘in good

repair’ in 1709? so James Bateman’s decision to demolish it and build another

in temple form on an axis with the front door of his new house (even at the

cost of an altar facing due west) can be seen only as an act of ruthless, but

inspired, landscape gardening.

In 1752 Bateman moved into the smaller house had had just built for himself at

Claxby, two miles from Well, leaving the big house for his only daughter Anne,

and her husband Samule Dashwood. Their son Francis Bateman Dashwood

who inherited in 1793 built a new wing, however he was in serious debt by

1800, more and more of the estate was mortgaged and finally his heirs were

forced to sell the whole property in 1836.

In 1836 the purchaser Nisbet Hamilton, an MP and Chancellor of the Duchy of

Lancaster, whose daughter Mrs Hamilton Ogilvey in turn sold the estate in

1914 to Major Walter Rawnsley.

In 1925 the Rawnsleys decided to rebuild the burnt south wing of the house,

Guy Elwes later contributed the columns and altered the pannelling. A fire in

1845 had gutted the hall and staircase as well as destroying the orginal

saloon. Guy Elwes changed the internal layout during the rebuilding.

The Doomesday Book and other records of Well

Well was a settlement in Domesday Book, in the hundred of Calcewath and

the county of Lincolnshire.

It had a recorded population of 19 households in 1086, and is listed under 2

owners in Domesday Book:

1. Land of Bishop Odo of Bayeux

Households: 2 villagers. 1 freeman.

Land and resources: Ploughland: 0.4 ploughlands.

Owners: Tenant-in-chief in 1086: Bishop Odo of Bayeux.

Lord in 1086: Losoard <of Rolleston>.

Lords in 1066: Otbert; Thorulf.

2. Land of Gilbert of Ghent

Households: 12 villagers. 4 freemen.

Land and resources: Ploughland: 3 ploughlands. 2 lord's plough teams. 1

men's plough teams.

Other resources: Meadow 1.5 acres. Woodland 22 acres. 1 mill, value 15

shillings.

Valuation: Annual value to lord: 7 pounds in 1086; 8 pounds in 1066.

Owners

Tenant-in-chief in 1086: Gilbert of Ghent.

Lord in 1086: Rademar.

Lord in 1066: Tonni <of Lusby>.

1626 Well estate is passed to the Willoughby family, Robert, the twelfth Baron

Willoughby de Eresby being created first Earl of Lindsey by Charles I in 1626.

During the Civil War of the 1640s the Earl of Lindsey, a Royalist, was forced to

sell Well to a Parliamentarian, Colonel William Wolley who occupied the

estate.

After the Restoration in 1660 the Wolleys kept their land but sold it in 1695 to

Anthony Weltden, an explorer-trader who had worked for the East India

Company. His son Anthony had succeeded by 1715.

1720 James Bateman, second son of Sir James Bateman of Shobden Court

(qv) acquired Well c 1720, possibly from his future father-in-law Sir Robert

Chaplin who had been ruined by the South Sea Bubble in 1720.

James Bateman's only child, Anne married Samuel Dashwood in 1744 and

they were given Well in 1752 when James Bateman moved to a smaller house

in Claxby. Anne and Samuel's son, Francis Bateman Dashwood (d 1825)

inherited in 1793. The village underwent considerable up heavily during this

time as the village was demolished and a new village built in it’s present

position. But the villages had lost their church. A new church was built - see

the web page on the church

Debts forced Francis’s heirs to sell the estate in 1836 to the Right Honourable

R A Christopher Nisbet-Hamilton, MP who purchased the manor and several

other estates.

The Hall was being let by 1856 to Thomas Turnell Cartwright.

Mr Christopher Nisbet-Hamilton's daughter, Mrs Hamilton Ogilvy inherited in

1876 and sold Well in 1914 to Major Walter H Rawnsley who had rented Well

Hall for several years.

Major Rawnsley's son, John Chaplin Rawnsley married Susan Reeve in 1925.

John Chaplin Rawnsley's widow died in 1974 and the estate passed to their

nephew, John Reeve.

The Hall was then sold and became a school, in which use it (2000) remains;

the grounds are in private ownership.

1881 Census Click here to see a transcript of the 1881 census

The population of the civil parish was 166 at the 2011 census, including the

hamlet of Claxby St. Andrew.

In Alford Francis Cooke’s diaries mention Well

1866 May 23 Rook shooting at Well, only 8-10 rooks each, poor sport.

1867 May 24 Rook shooting at Well, middling for rooks.

1876 Poaching affay at Well, N shot at but didn’t hurt him. N downed

Middleton, took his gun and brace of pheasants.

Claxby Manor House in Claxby St Andew) (also known as Claxby Hall) was

built around 1760, reputedly for Samuel Dashwood as the Dower House to

Well Hall. It later became the vicarage, and is a Grade II listed building.

What is now known as Claxby Manor House is an entirely different building

situated across the valley.

In 1870-72, John Marius Wilson's Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales

described Well like this:

WELL, a parish in Spilsby district, Lincoln; 1½ mile SSW of Alford r. station.

Post town, Alford. Acres, 2,110. Real property, £2,454. Pop., 99. Houses, 17.

W. Hall is the residence of T. Cartwright, Esq. There are three ancient British

barrows; and about 600 Roman coins, in two urns, were found in 1725. The

living is a rectory, united with Claxby, in the diocese of Lincoln. Value, £400.*

Patron, the Right Hon. R. A.N. Hamilton. The church is modern, in the form of

a Grecian temple.

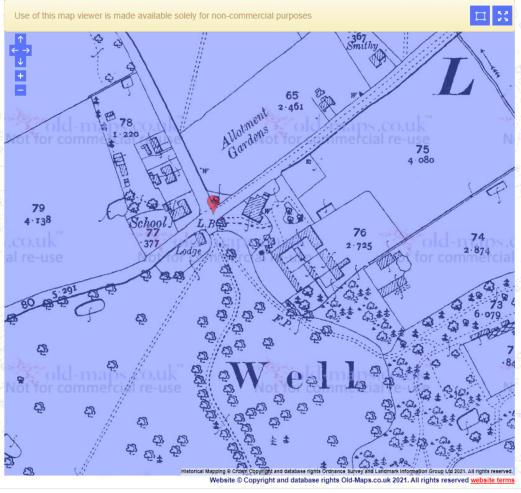

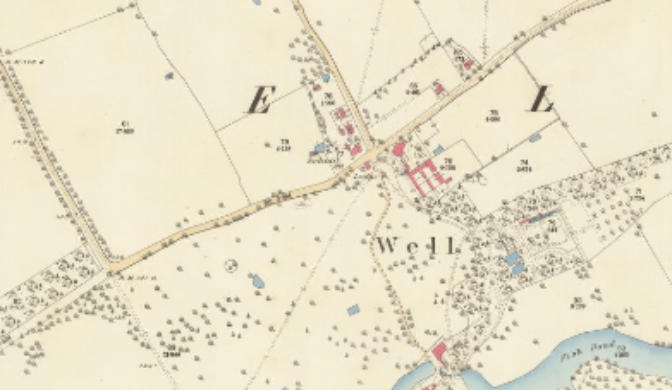

A map of Well showing the School and the Smithy dated 1890/91